International Development

UK Social Enterprise Report: The Big Issue Invest

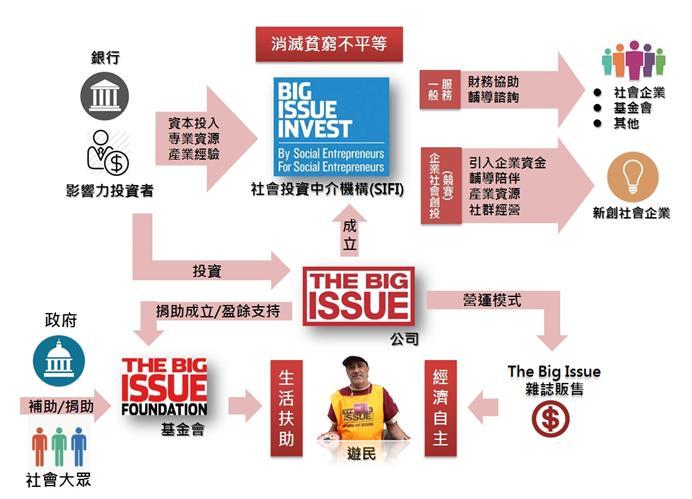

To encourage charity organizations and businesses to join the ranks of social reform to eradicate poverty together and help social enterprises to grow, TBI established its investment-oriented subsidiary: The Big Issue Invest.

UK social enterprise report: The Big Issue Invest

Organization introduction

The Big Issue is a world-renowned social enterprise, which employs a unique method to help the homeless become self-sufficient by hiring them to sell magazines on the streets. So far, the method has been applied to nine other countries in the world, which includes Japan, South Korea and Taiwan in Asia. KIMO founder Li Chu-Chung introduced Taiwan’s The Big Issue. The magazine’s hipster-oriented editorial style focuses on the readers of the “Foolish Generation” aged between 20 and 35. Since its inception in April 2010, the sales location has been expanded southwards from Taipei all the way to Taichung and Kaohsiung, where TBI vendors can be seen in over 70 busy public transport or campus locations throughout the countries. Founder John Bird also visited Taiwan under the invitation of a domestic private organization. At the age of 70, Mr. Bird is a very humorous and witty individual, thus his speech was full of dramatic tension, and he exhibited exuberant enthusiasm about social enterprises.

After TBI became a success, John Bird and his team are still constantly contemplating ways to expand their social impact. They understand that that the power of one is limited, therefore in order to encourage charity organizations and businesses to join the ranks of social reform to eradicate poverty together and help social enterprises to grow, TBI established its investment-oriented subsidiary The Big Issue Invest.

The interview was originally going to be attended by The Big Issue co-founder John Bird and Big Issue Invest CEO Nigel Kershaw at the Simmons & Simmons – a management consultancy also renting out conference rooms. After walking through a maze of corridors full of artwork, we finally reached the conference room, only to be greeted by tea and stationery.

Just when we were busy appreciating the comprehensive design of the conference room, BII’s CEO Nigel Kershaw entered through the door. The elegant English gentleman told us that his partner John Bird’s schedule was considerably delayed by his health inspection this morning and he could not attend the meeting, so he would be chatting to us alone. Nigel has never been to Taiwan and hence had limited knowledge about social enterprise developments in the country. After we brought him up to speed briefly, he was able to immediately provide Taiwan with suggestions from BII’s point of view. Nigel spoke in clear and charismatic British accent. The following is the first person account of the meeting with Nigel.

Inchoate Social Enterprise Investment

Big Issue Invest was founded and owned by parent company – The Big Issue in 2005. Currently it has a total investment of approximately £20 million across more than 160 social enterprises, and it is in the process of preparing for the next £5 million investment fund.

Speaking of investing in social enterprises, the first key aspect is to review how they generate social impact. As far as I’m concerned, how to make money is relatively easy to describe, but how to measure the social enterprises’ social and financial benefits is the most crucial. Without measurement, the fundamental meaning of this endeavor is lost, because you don’t even know what your investments have helped to create. The difficult part is that many social enterprises are young and full of innovative elements; if you see an unprecedented, novel idea, how do you go about measuring it? Yesterday at the G8 social investment forum, I mentioned that I was afraid if BII’s investment targets were brought to the table to be openly discussed, everyone present would raise both their arms in opposition, because they were simply too new and a lot of the ideas are just out of this world. It is precisely because of this that we need to emphasize the measurement of benefits.

Actually, I’m not a big fan of the term social enterprise myself; if possible, I prefer to use the term social business. I feel that the word “enterprise” somewhat limits our imagination about the form and appearance of social enterprises, so we unavoidably view them from an enterprise point of view.

A VP of BII is an expert in microloans, so we utilized the balanced score card as the basis to design our evaluation tool and place the emphasis on how to evaluate the entrepreneur and the team. Evaluation priority: The first is whether the project generates social impact; the second is whether the startup team is capable of putting their dreams into practice; the third is to inspect whether it is a good business model; lastly, how it performs in terms of revenue. The thinking model behind this sequence is totally different to the general investment business model, this is also the organizational spirit that the BII’s slogan on Nigel’s business card intends to express: For social entrepreneurs, by social entrepreneurs.

Experts engaged in general investment usually come from a financial professional background and have received countless professional training. Even if they are involved in the social investment market, the first figure they look at after opening the business proposal is still revenue. We all know that social enterprises do not produce outstanding results during the early stages of development, so these experts are always eager to tell the social entrepreneurs “You should do this, you should do that, otherwise how are you going to support yourself and give back to the investors?” However, financial operation is more of a means to an end rather than the end itself. Hence, for us social entrepreneurs, working with financial experts is like going to a battle for the entire day, because they sure know how to push our buttons. I keep telling them that you should try to understand what social entrepreneurs are thinking about rather than talking about business models and looking at revenue numbers. Our goal is to change the world and make poverty disappear from the face of Earth, not simply to care about financial performance, because it will only mean that we want to make money. As a result, it is crucial to let social entrepreneurs get acquainted with financial experts during the early stages of development, as it not only enables financial experts to understand what social entrepreneurs want but also let social entrepreneurs understand what management is all about and the risks involved .

Corporate social venturing method

Yesterday at the G8 I introduced the concept of Corporate Social Venturing (CSV). In the early stages of our startup, we wanted to invest in social enterprises that intend to improve the lives of homeless people. At the time, we had numerous corporate partners like PwC from the accounting industry (which also sponsors SEUK’s office space) and British Telecom etc. Back then, our focus was how to encourage participation from the large corporations not only by investing but also to utilize the corporations’ resources to facilitate the growth of social enterprises.

Have you seen the reality show Dragon’s Den? (Editor’s note: Using venture capital investment as the theme, entrepreneurs pitch their ideas on the stage. After elimination rounds, the dragon played by an investor chooses who wins the investment to bring the show to a climax. The show format originated in?the Japanese TV reality show “Money Tigers: No Challenge, No Success!” Basically, CSV is a two-day entrepreneurship contest where we accept proposals from 1~200 social enterprises and select 10 of them to be invested.

However, we do not criticize the social entrepreneurs directly on the stage whether it is a great idea or business model and tell them “Sorry mate, you are out of here!” Rather, we invite senior managers from our large corporate partners to become the jurors. Through the competition process, the entrepreneur teams and their corporate partners work together to build their respective business models. Furthermore, at the end of the contest we will ask our corporate partners to adopt their entrepreneurial teams for at least three years, thus the values created by CSV are not merely to let the contestants win investment capital but to make it an interesting and fulfilling thing to do.

This is not simply about public welfare and the fulfillment of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) where money is simply donated. Now, they are also participants in the contest; the process not only allows them to give but also learn from the social entrepreneurs. For instance, who would have thought there is a group of people so passionate about transforming the world, not driven by the ultimate goal of making money? Certainly, employees in the corporations will be touched and the corporate culture will become more humble, in turn generating bilateral value feedback.

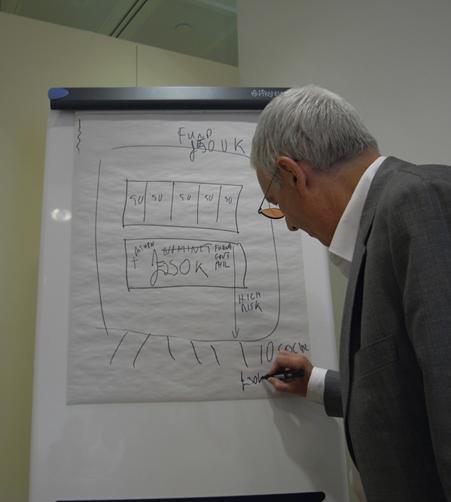

Next, I will draw a diagram to explain CSV’s approach. For each contest, we will always first establish a theme. In the early years, we focused on improving the lives of homeless and the latest theme is Tech for Good. BII will raise a certain amount of money beforehand as the basis (for example, quarter of a million pounds), then we began searching for five major corporations willing to collaborate based on the theme. Each corporation will sponsor £50,000 to create leverage; each business only sponsors £50,000 to participate in a half a million pounds entrepreneurial activity.

The fund is used as an investment rather than a loan, and the appropriation of fund will first be done through the £250,000 fund raised by BII in the beginning. After the contract period of three years has passed, the outcome of the social entrepreneurial teams are examined, some will fail (or last less than three years). The investment loss is recognized through BII’s basic fund first; since the basic fund bears the highest risk, the major corporations’ willingness to partake in the event is also significantly increased.

Total participation to keep track of the partners

Besides corporate partners acting as the jurors for the CSV contest, we also invited several well-known experts or consultants in the industry. In the beginning, we accepted online registration, where the contestants must propose their business plans according to our stipulated format, perhaps a page or two written information supplemented by a two-minute self-introduction video. Thereafter, we will arrange the jurors to conduct the first round of discussions via Skype online with the contestants. After that, we will convene a roundtable meeting to start eliminating the more inappropriate proposals and narrowing the number down to about 15. From those, 10 finalists will be selected. BII has implemented over four CSV contests, five if we include the one in Australia. BII has also benefitted tremendously because we learned how to look out for outstanding projects and teams, and our judgment is becoming increasingly accurate.

During the judging process, the senior managers interact frequently with the entrepreneurial teams. As the jurors provide their recommendations, they are already secretly choosing their future investment targets. When we announce the final list, sometimes multiple corporations can select a team, and negotiations will be made to resolve the situation, so that each team will receive investment from a corporation or guidance by experts who have adopted them. If negotiation fails, sometimes we have to let more than two corporations adopt the same team.

We also observed two interesting phenomena. The first is that when a certain team receives adoption application from multiple corporations, corporations intending to adopt the same team will exchange opinions about the proposal during the selection process. The discussions often lead to work specialization; for example, if corporation A specializes in design and corporation B’s forte lies in marketing, they will offer their suggestions to the entrepreneurial team according to their respective areas of expertise during the selection process, thereby creating a cross-corporation community with the contestant. The collaborative community relationship will continue to exist after the contest to let the contestant receive diverse company and guidance. The second phenomenon is that if there are competitors from the same industry among the participating companies, a new competitive relationship will develop during the future accompaniment process.

For example, our corporate partners in the Tech for Good theme are Salesforce (CRM and cloud services) and Merrill Lynch (securities); both not only place great emphasis on the application of technology in rendering their services but also focus on technology in regards to social enterprise investment. In addition to competition in the industry, the two corporations will secretly pay attention to the development status of their competitor in team adoption and strive to extract other available resources from their companies to assist their respective entrepreneurial teams. At the end, the resources invested may be far more than the initial investment, because they do not wish to lose to each other even in this contest. The reason being that if their adopted teams go out of business, imaging what a huge humiliation it will be for them!

For many entrepreneurship competitions, the teams are not followed up after the prizes are awarded to see if they have actually started their businesses. It is also not uncommon to hear that entrepreneurial cash prizes are changed to expensive consumer electronics or travel expenses. For teams selected by CSV, it is imperative that the money is used to start-up a business. Furthermore, the goal of participating in the contest is not just about the money. More accurately speaking, they are receiving a complete entrepreneurial resource package; it is like accompanying children to grow up into adults. Along the way, you will be accompanied, helped and adequately guided to obtain the right energy and nutrients. The finalists of CSV will become a genuine social enterprise and BII will continue to monitor its subsequent developments.

People who have started their own business will know that the initial stages are absolutely the most challenging, not to mention social enterprises with double or triple bottom line. In addition to capital, mentor, magnate, it is also important to have like-minded people constantly encouraging one another and offering psychological support to let the team forge ahead bravely. Consequently, we do not simply leave the ten finalist teams with their adopters after the contest is over, we invite them to gatherings on a regular basis and provide them with a platform to form a community, where they can care about, stimulate one another or share their thoughts. As a result, many teams have developed strong bonds. So far, CSV has assisted over 34 teams, of which 30 teams are still in operation. Even by conventional venture capital investment standards, the survival rate of these social enterprises is still staggeringly high.

Suggestions for Taiwan

Although CSV investment funds are raised by BII, but to persuade the large corporations to sponsor money for investment from the outset is virtually impossible. Fortunately, BII initially received a grant from the government’s Department for Communities and Local Government (authority for caring about the homeless), which took care of our dilemma of raising a large capital before producing any result. Therefore, after CSV has made a reputation for itself, our endeavor to seek funding from various parties became relatively simpler (As a matter of fact, the first three rounds of the contest was primarily based on government funding).

During the early stages of social enterprise development in Taiwan, if there is a dedicated agency overseeing policy development and funding is available, perhaps you can raise the first basic fund with the government agency setting the theme (for example, Ministry of Health and Welfare – which looks after the industry). After that, adopt CSV’s model to discover and facilitate more social enterprise development. You mentioned that most large corporations in Taiwan still appear to be speculative about participating in and promoting social enterprise development. However, the advantage of CSV is that the first investment can be borne entirely by the government, whereas the corporations and other experts or consultants only need to partake in the selection and adoption process – which is a relatively less costly endeavor. When the corporations realize the value of this contest, various private capital will pour in and the entire model can be transformed to a privately run event. This is very feasible because we have experience to prove that it works.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Please attribute this article to “Workforce Development Agency, Ministry Of Labor”.